It is common in therapy to hear people describe a similar loop: on the one hand, they want to feel appreciated and indispensable; on the other, they feel suffocated by constant requests for help, favors, and responsibilities that seem to multiply endlessly. Many tell me: “Everyone needs something from me, and I just can’t take it anymore.”

Take the case of Gustave. He is a brilliant, reliable person who is always ready to solve problems. He is the kind of person others turn to when something needs to be done well. But over time, this very reliability can become a burden. The sense of being “indispensable” begins to feel stifling, and the desire to feel recognized turns into frustration and resentment.

Listening to his story, a paradox emerges. On the one hand, there is a longing for connection and validation, and the belief that doing everything “perfectly” will lead to the appreciation they desire. On the other hand, there is a deep sense of pressure and dissatisfaction: the feeling of having no choice but to meet others’ expectations. The harder they strive to be flawless, the more the demands seem to grow.

Looking more closely, it becomes clear that many of these demands, perceived as “external,” are actually fueled by internal expectations. People like Gustave often step in to help without being asked, fix problems that no one requested them to address, and take on responsibilities that could easily be delegated. They distrust the way others handle tasks and end up reorganizing them. In doing so, they trap themselves in a vicious cycle: the more responsibilities they take on, the heavier the burden of expectations feels, and the more resentment toward others grows.

Gustave’s experience is not unique. This dynamic is more common than one might think, and the line between what others ask of us and what we demand of ourselves is often much thinner than it seems. The good news is that it is possible to recognize and break free from this loop, regaining a sense of balance and freedom.

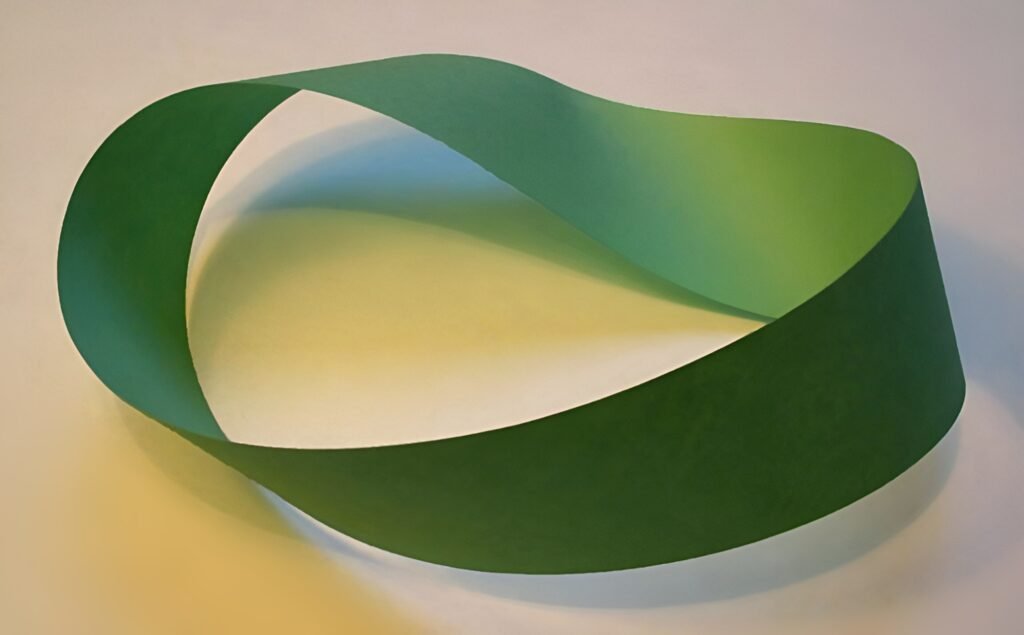

To better understand this dynamic, we can turn to an unlikely source: a mathematical object known as the Möbius strip.

What is the Möbius strip?

The Möbius strip is a mathematical shape described independently by Johann Benedict Listing and August Ferdinand Möbius in 1858. It is a simple yet fascinating object: a surface with only one side and one edge. You can create one by taking a strip of paper, twisting one end by 180 degrees, and joining the ends together.

What makes the Möbius strip unique is its paradoxical structure. If you trace a line along the surface, you will end up covering “both sides” without ever crossing an edge—because, in truth, it has only one side.

Why Lacan turns to the Möbius strip

For Jacques Lacan, the Möbius strip offers a way to think about how “inside” and “outside” are continuous in psychic life. The image we call “mine,” the gaze of others, the words we use about ourselves, and the ideals that guide us all lie on the same twisted band. We move along it daily, sometimes convinced we’ve changed sides, when in fact we are traveling the very same surface.

Applied to the case

His predicament reads like a Möbius path. On one “side,” he experiences the weight of others’ demands. On the other, he enforces an inner standard of perfection and control. But there is no clean crossing between the two: the standard that organizes his actions also generates the situations in which he feels besieged. Trying to escape by “doing even better” or by “pushing back harder” often brings him back to the same place—another lap on the band.

This is not about blame. It is structural. The wish to be reliable, the satisfaction of competence, the desire to be seen, and the fear of failing are knotted together. The Möbius metaphor helps us notice how self‑imposed standards and perceived external pressures can be two faces of the same demand.

In therapy—just a few words

Therapy does not aim to separate inside from outside once and for all. Rather, it helps make the twist visible. Recognizing the twist does not dissolve contradictions, but it creates a margin of freedom. Naming how one’s position invites certain responses, and letting others do things their way are small shifts that can alter the whole surface of everyday life. Sometimes a brief pause—waiting to be asked before intervening—opens a different route along the band.

If you find yourself caught in a similar Möbius-like loop of expectations, therapy can offer a space to pause, reflect, and discover new ways of navigating these twists. Even small changes can lead to profound shifts in how you experience both yourself and others.