ADHD: Unraveling the Roots – A Psychoanalytic Perspective

If you're wondering if you have ADHD, you're not alone. Many people experience similar struggles.

1. I think I have ADHD. How can I be sure?

ADHD, or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, is not a disease with a clear-cut cause, but a label for a cluster of experiences and behaviors. It's not something you definitively "have" or "don't have." It's better understood as a constellation of symptoms—restlessness, inattention, impulsivity, forgetfulness, anger, and daydreaming—which are common experiences in our stimulus-filled world.

Before accepting this label, explore the function of these experiences in your life. What specific difficulties are you facing, and in what contexts? What purpose might restlessness, inattention, or impulsivity serve? Do these behaviors help you avoid anxiety, express anger, or manage difficult emotions? What thoughts and feelings are you protecting yourself from?

Remember, ADHD isn't a fixed condition or personality trait. It's a syndrome, a label applied to overlapping symptoms that aren't unique to ADHD and can also manifest in experiences like anxiety and depression. Diagnosis often relies on subjective questionnaires, and these experiences can shift over time and context. You might struggle in rigid environments, yet thrive in stimulating ones. Psychoanalysis can help you understand the roots of your difficulties, moving beyond simple diagnosis to explore the underlying causes.

2. What exactly is ADHD? It seems like everyone has it these days!

ADHD is a syndrome, not a disease. It's a label applied to a set of symptoms that have always existed but are now grouped under this acronym. It's talked about a lot, perhaps too much. This can lead to overdiagnosis and medicalization of behaviors that might be expressions of discomfort or difficulty adapting. ADHD doesn't describe a psychic structure with specific mechanisms (like obsessive-compulsive disorder, paranoia, or others). It gives a name to various maladjustments, to something hard to define.

Saying someone has ADHD doesn't solve the problem: which aspect of ADHD is predominant? Restlessness, inattention, impulsivity, anger, relationship difficulties? This is what needs to be understood through clinical interviews. ADHD is a way of naming something (a fundamental, yet elusive, aspect of experience) that is not well defined. There's an emphasis on action, reaction, and a difficulty thinking and processing emotions. The label can provide temporary relief but doesn't answer the fundamental question: which aspect of ADHD is predominant in your experience?

Even without the ADHD label, if restlessness, inattention, or impulsivity cause you distress, a psychoanalytic approach can help you understand its origin and find a new balance. In what contexts do you feel most uncomfortable?

3. Is ADHD a permanent condition?

No, ADHD is not a static condition, a fixed label, or an incurable disease. It's not something you definitively "have" or "don't have." The symptoms—the restlessness, the inattention, the impulsivity—can shift and transform throughout life, influenced by our experiences, our relationships, and the ever-evolving demands of the world around us. A child's hyperactivity might be a strong attempt to capture a parent's attention; in adulthood, that same dynamic might manifest as a relentless pursuit of external validation. The inattention that frustrated teachers in school could, in a different context, become the hyperfocus that fuels creative breakthroughs.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, these symptoms are not merely signs of a neurological disorder, but expressions of unconscious desires, unresolved conflicts, and the ongoing struggle to find our place in the world, particularly in relation to others. What might appear as a deficit of attention could, in fact, be a profound difficulty in sustaining attention to the Other—a consequence of early relational experiences where true connection felt elusive or conditional.

As we move through life, the specific ways these underlying dynamics manifest can change, but the core questions—the questions of recognition, belonging, and desire—often remain. Psychoanalysis offers a space to explore these questions, to unravel the complex interplay between our internal world and the external pressures that shape our experience of ADHD. It's not about "curing" the symptoms, but about understanding their meaning, their function, their history, and their potential for transformation.

While psychoanalysis offers valuable insights into the underlying dynamics of ADHD, it's also important to consider the complexities of diagnosis. ADHD symptoms are not unique to this condition and often overlap with other clinical presentations, such as anxiety, depression, learning disabilities, trauma, or relationship difficulties. What initially appears to be ADHD, upon closer analysis, could be a manifestation of these other issues. Psychoanalysis can help distinguish between the different possibilities and identify the root of the problem. As the cause of the discomfort is understood and processed, the ADHD label can lose importance, giving way to a deeper understanding of oneself and one's ways of functioning.

4. Why is everyone talking about ADHD these days?

The ADHD acronym owes its popularity to finally giving a name to experiences and symptoms that are difficult to categorize. It offers a sense of recognition, a way to articulate a feeling of "not fitting in" that perhaps resonates with something unconscious, something difficult to name. Many people feel relieved to finally have a diagnosis, something that allows them to say, "I have this, this is why I am this way." This can alleviate shame and validate the experience of difference, offering a sense of belonging to a community of people with similar struggles. Furthermore, the diagnosis of ADHD has spread rapidly thanks to social media, where shared experiences and self-diagnosis can create a sense of solidarity, even if premature. ADHD has become a broad umbrella, encompassing a range of behaviors that might be seen as unconventional or even rebellious, particularly in a society that prizes conformity and self-control.

However, arriving at this diagnosis, at this label, is not in itself a solution. While it can be a first step towards seeking help, it can also become a way to avoid deeper exploration. It can be a way to reduce shame ("It's not my fault, it's my brain that works this way!"), or to justify seeking a quick fix. Medication, by promising a rapid solution, can create the illusion of eliminating the symptom without addressing the underlying psychic dynamics. Like a painkiller that silences the message of pain without healing the wound, medication can offer temporary relief, but not true transformation.

A psychoanalytic approach, on the contrary, invites us to explore the meaning and function of these symptoms—the restlessness, the inattention, the impulsivity—within the context of the individual's unique history and unconscious desires. It encourages us to go beyond the label and explore the personal meaning of the discomfort, recognizing that true change requires engaging with the root causes, not just managing the surface manifestations.

5. What are the main symptoms of ADHD?

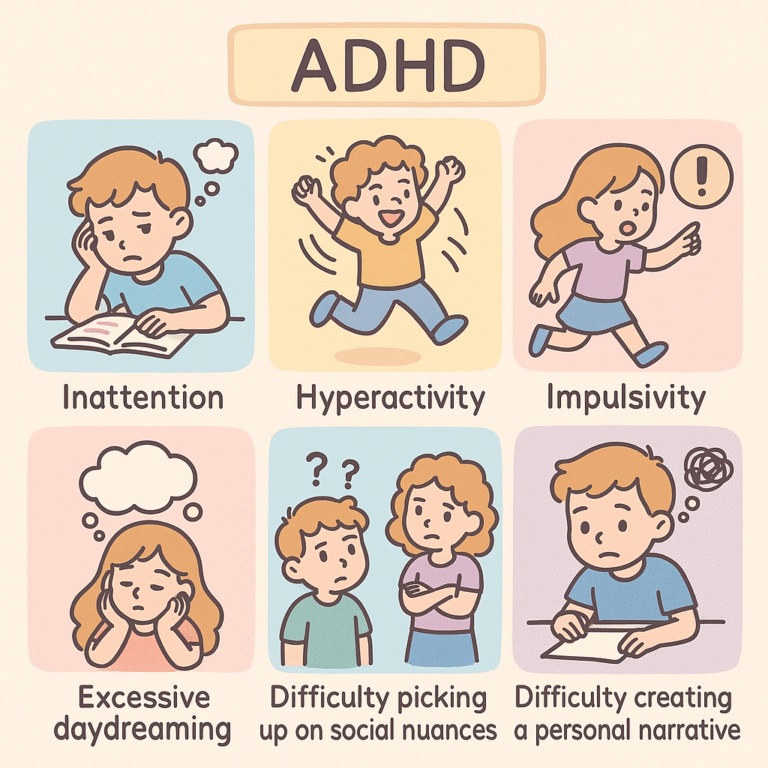

The main symptoms of ADHD are varied and can manifest differently in children and adults. Some of the most common symptoms include:

• Inattention: Difficulty focusing on details, following instructions, organizing tasks and activities, easily distracted. This can be frustrating for both the individual and those around them, often leading to misunderstandings and accusations of laziness or apathy. From a psychoanalytic perspective, this difficulty sustaining attention might be linked to an unconscious avoidance of certain thoughts or feelings, a way of protecting oneself from internal conflict.

• Hyperactivity: Motor restlessness, difficulty staying still, excessive talking. This constant motion can be seen as an attempt to discharge an excess of energy, a physical manifestation of an internal restlessness that can be difficult to contain. Psychoanalytically, this might be understood as a way of managing an underlying anxiety or a difficulty regulating one's own impulses.

• Impulsivity: Difficulty controlling impulses, interrupting others, acting without thinking about the consequences. This can lead to impulsive behaviors that create interpersonal challenges and reinforce feelings of shame and regret. From a psychoanalytic perspective, impulsivity can be seen as a difficulty with symbolic thought, a tendency to act out rather than process emotions through language.

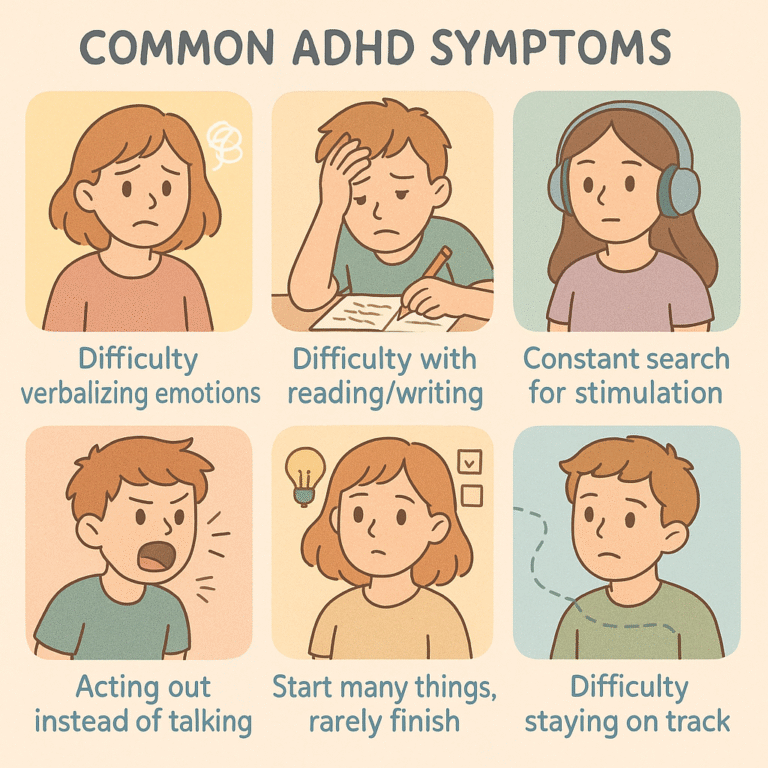

In addition to these core symptoms, some individuals may experience difficulties in verbally expressing emotions and thoughts, a tendency towards action rather than reflection, and a constant search for external stimuli. They may also struggle with a sense of feeling scattered, without a center of gravity, lost when alone with themselves, and sometimes even experience difficulties in reading and writing. There is, therefore, a considerable difficulty in "reading" the world, in making sense of one's own and others' experiences. This difficulty can be understood, from a psychoanalytic perspective, as a struggle to symbolize experience and create a coherent narrative of oneself.

These seemingly disparate symptoms can be fragments of a single story, of a question that has not yet found its form. Often, there is a marked disconnect from one's unconscious desire, a remaining trapped in the position of object for the Other (feeling defined by the desires and expectations of others), a continuous search for external attention to compensate for personal insecurity, or the continuous search for recognition that never arrives. The overstimulation of modern society, the crisis of symbolic authority, the difficulty of adults in assuming clear educational positions, the medicalization of discomfort... all this contributes to creating fertile ground for the emergence of the symptoms we find under the umbrella of ADHD. In a world that bombards with stimuli and then demands "sit still and concentrate," the individual with ADHD can struggle to find their place.

These seemingly disparate symptoms can be fragments of a single story, of a question that has not yet found its form. Often, there is a marked disconnect from one's unconscious desire, a remaining trapped in the position of object for the Other (feeling defined by the desires and expectations of others), a continuous search for external attention to compensate for personal insecurity, or the continuous search for recognition that never arrives. The overstimulation of modern society, the crisis of symbolic authority, the difficulty of adults in assuming clear educational positions, the medicalization of discomfort... all this contributes to creating fertile ground for the emergence of the symptoms we find under the umbrella of ADHD. In a world that bombards with stimuli and then demands "sit still and concentrate," the individual with ADHD can struggle to find their place.

Nuance in "Reading" the World:

It's important to understand that the difficulty with nuance often attributed to individuals with ADHD is not simply a matter of seeing the world in "black and white" terms. Instead, it may involve a heightened sensitivity to certain stimuli, while other nuances are missed. This can lead to misinterpretations of social cues, difficulty understanding irony or sarcasm, and a tendency to take things literally. This can create challenges in navigating social situations and forming meaningful connections. From a psychoanalytic perspective, this difficulty with nuance might be linked to early childhood experiences where inconsistent emotional responses may have led to difficulties recognizing and interpreting subtle emotional cues.

The goal should not be so much to arrive at a diagnosis (which is only a starting point), but to interpret these symptoms in light of the individual's history. This is possible during an analysis. Often there is a difficulty in translating one's inner world into words, in constructing a narrative of one's experience, and a predilection for non-verbal forms of expression, such as music or the visual arts. Physical exercise and routine can offer support, but true transformation occurs through the processing of unconscious conflicts and ambivalence.

Specific Difficulties in Different Areas (with psychoanalytic lens):

• Difficulty with words: They tend to replace words with impulsive actions (such as physical aggression, avoidance, or emotional outbursts) instead of verbalizing what they feel. Their language is often less symbolic, with difficulty translating emotions into more articulated narratives, presenting a difficulty in narrating their own story, which appears fragmented. This can be understood psychoanalytically as a difficulty symbolizing emotions and experiences, leading to a reliance on action rather than verbal expression.

• Writing and reading (disorganized): Their attention can be inconsistent, shifting between hyperfocus and distraction. They might read only what intensely interests them and struggling with texts that don't immediately resonate. Even with topics that fascinate them, they may struggle to articulate why they are so drawn to them, finding it difficult to connect their passions to their personal history. This difficulty making meaning, especially from a "third" perspective (that is, from the perspective of others), can manifest in challenges with reading and writing. Psychoanalytically, this can be seen as a difficulty integrating different perspectives and understanding the subjective experiences of others.

• The world of fantasy: Often these individuals get lost in their fantasies, indulging in an imaginary world that can offer solace and escape from the challenges of everyday life. These fantasies may be populated by themes of aggression, revenge, or idealization. Unlike a more playful or adaptive form of imagination, these individuals may sometimes blur the lines between fantasy and reality, oscillating between romantic idealization and anger at what deviates from their internalized ideals. They might describe themselves as "delusional," (or “delulu”, out of touch with reality) deeply immersed in their inner world, with a diminished interest in the external world and the internal world of others, which can appear alien, indecipherable, or simply uninteresting. From a psychoanalytic perspective, this immersion in fantasy can be understood as a defense mechanism, a way of protecting oneself from painful emotions or difficult realities.

6. Why is ADHD so common today?

ADHD diagnoses are constantly increasing. In the late 1990s, researchers estimated that ADHD affected about 3% of the youth population. Year after year, diagnoses have increased for various reasons (more people are being tested, social media contributes to popularizing this diagnosis, etc., add other causes) and in recent years we have reached, depending on the studies, percentages six times higher than the initial ones. Not only that, but reading social media, forums, hearing people around, it seems that now everyone has (or thinks they have) ADHD. The increase in ADHD diagnoses is a complex phenomenon. Increased awareness, influence of the pharmaceutical industry, cultural and technological changes, broad diagnostic criteria... all contribute to creating the impression of a real "epidemic." But psychoanalysis invites us to reflect: is ADHD perhaps the symptom of a society that, in trying to control everything, paradoxically produces more and more perceived "uncontrollability"?

Does the hyperactive individual, with their body that "doesn't stay still," embody precisely what escapes every attempt at total control? We live in the age of distraction, the illusion of total control, performance at all costs. Today's "fluid" society, with its promise of unlimited freedom and constant exposure to technology, can generate disorientation and loss of connection. Technology, with its rapid and fragmented stimuli, the pressure to always be "connected," and the difficulty in maintaining concentration on a single task, further amplifies these dynamics. ADHD, with its (unconscious) rejection of rules, embodies the failure of this ideal of control and performance. The body that "doesn't stay still" is a silent cry, a "no" that rebels against the demand for a normality that suffocates desire. Modern symptoms - panic attacks, autism, addictions, borderline personality disorder, ADHD - testify to this difficulty in finding a place in the world. Hyperactivity, in particular, can be interpreted as an uncontained excess of drive, a consequence of the crisis of symbolic authority, the decline of the function of the "father" as limit and containment.

7. I have always been like this. Does it mean I developed ADHD as a child and was never diagnosed?

It is possible that some traits have been present since childhood but manifest differently at various stages of life. Psychoanalysis considers psychic development as a continuous process, in which themes such as the need for recognition, separation, regulation of distance in relationships, and confrontation with limits reappear in different forms from childhood to adulthood. An analytic path can help to understand how these themes intertwine with the symptoms of ADHD, to understand which issues are at an impasse (from which the symptoms originate) and how to overcome them.

In short, the important thing is not so much to arrive at the diagnosis of ADHD (as with any diagnosis) but to try to articulate those parts of ourselves that feel elusive or difficult to understand and that we may be able to experience as free, unfiltered energy, as anger, restlessness, boredom.

8. What is the role of emotions in my difficulty concentrating?

Difficulty concentrating, often labeled as "inattention," is not simply a "technical" problem, but a way of avoiding difficult emotions. Restlessness, "mind-wandering," can be unconscious attempts to distract oneself from anxiety, anger, sadness, shame, or other emotions that are difficult to recognize and name. This difficulty in "being with oneself" can be linked to an "inner emptiness" that one tries to fill with external stimuli. A psychoanalytic approach can help you think about these emotions, to name them, without having to resort to the weapon of distraction every time.

9. How do my relationships influence my symptoms?

Our relationships, starting with our primary relationships with parental figures, shape our way of being in the world and profoundly influence our symptoms. In ADHD, difficulty concentrating, impulsivity, and restlessness can be linked to dysfunctional relational dynamics, such as difficulty establishing clear boundaries, the constant search for external approval, fear of abandonment, or difficulty managing ambivalence towards reference figures. The child or individual with ADHD can remain trapped in the position of object for the other, continually seeking external confirmations of their worth. Psychoanalysis helps to understand how past relational experiences influence the present, allowing one to be more present and build more authentic relationships.

10. What prevents me from "being with myself"?

The difficulty in "being with oneself," in tolerating solitude and inner silence, is a central aspect of ADHD. Hyperactivity and the continuous search for external stimuli can be a way of avoiding confrontation with an inner emptiness, with difficult emotions or thoughts, with the fear of not being "enough." This can manifest as a difficulty in "naming what one feels" and "building a more solid relationship with one's inner world." Psychoanalysis offers a protected space where one can learn to listen to one's unconscious, to name what one feels, and to build a more solid relationship with one's inner world.

11. Is there a link between my hyperactivity/inattention and my family history?

Often, hyperactivity and inattention are linked to complex family dynamics. It is not simply a matter of identifying "blame" in the past, but of understanding how family experiences have contributed to shaping our way of being in the world and relating to others. In particular, psychoanalysis helps to identify those unexpressed questions that, not finding space to be formulated with words, manifest themselves through symptoms. Hyperactivity, for example, can be a way of asking for attention, of testing parental love, or of expressing difficulty in managing one's emotions. These questions, initially addressed to reference figures in childhood, can remain unconsciously active even in adulthood, leading us to repeat certain relational dynamics and always find ourselves in the same situations. Psychoanalysis offers a space to give voice to these questions, to understand their meaning, and to find new ways of responding, interrupting the vicious circle of repetition.

12. How can I learn to listen to my body?

In ADHD, the body often "speaks" through motor restlessness, difficulty staying still, and impulsivity. These symptoms can be read as messages from the body expressing an unexpressed discomfort, a difficulty managing emotions, a need for recognition, or a difficulty "feeling one's body and relating to the world." Hyperactivity can be a way to "create boundaries" between oneself and the external world when these boundaries have not been clearly defined in early relational experiences. Psychoanalysis helps to make sense of these messages, to understand the language of the body, and to reconnect with one's physical sensations.

13. Is therapy effective for ADHD? What type of therapy is most appropriate?

Psychoanalysis can be very effective. It does not simply "correct" the symptoms, but explores their meaning/function in the subject's history. It helps to give voice to what remains unexpressed, to understand the unconscious dynamics that fuel restlessness, impulsivity, and inattention. It offers a space for listening and processing, allowing one to find a personal way of managing their difficulties, not trying to "normalize" but to understand oneself better and find one's balance. Analysis, in particular, helps to interpret the symptom in its singularity, beyond the label, and to find a new position in relation to social demands, without being crushed by them. The challenge is to 'inhabit the social' authentically, that is, to find one's own way of being in the world, of relating to others, and of responding to social demands, without losing sight of one's needs, desires, and limits.

14. How does a psychoanalytic path for ADHD unfold?

A psychoanalytic path starts from the analysis of what creates discomfort, focuses on the exploration of the individual's inner world, particularly what is unconscious, on their significant relationships, and on their past experiences, but also their dreams and desires.

Through dialogue with the analyst, the patient can give voice to their thoughts, emotions, and fantasies, even the most difficult or confused ones. The goal isn’t to suppress symptoms, but to give expression to what underlies them—even when these causes are unconscious or unknown to the patient. By bringing these hidden factors to light, symptoms can lessen or even disappear, making lasting change possible. The frequency and duration of treatment vary depending on the case.

15. Is ADHD a brain problem?

ADHD is not simply a "brain problem." It is a complex phenomenon influenced by psychological, relational, and social factors. Many of those who claim to have ADHD say that "their brain works differently from neurotypicals." Initially, researchers thought that ADHD was indeed a brain problem, but recent studies seem to overturn this perspective and demonstrate that ADHD is not a brain problem, that the brains of those with and without ADHD diagnoses do not show visible differences, and that the issue is much more complex and cannot be reduced to a brain that functions "normally" or not.

16. Should I take medication for ADHD? What are the possible side effects?

The decision to take medication should be made in agreement with a psychiatrist, carefully weighing the benefits and risks. Various studies have shown that stimulant medications can improve attention in the short term (not as much in the long term), can help focus on boring tasks, and reduce impulsivity, but they do not resolve the underlying causes of the discomfort. Furthermore, they can have side effects such as decreased libido, anhedonia, and even dependence; some individuals report feeling emotionally "flattened," less sociable, or less happy.

It is important not to confuse apparent calmness (lack of symptoms, but general flattening of mood, feeling numb) with inner peace (being well with oneself)!

Next Steps:

If you'd like to explore this topic further, I offer a couple of free, commonly used, and reliable ADHD self-assessment tests on my website:

While these tests are not sufficient for a diagnosis, they can provide some helpful insights into potential areas of difficulty.

For personalized guidance and support, I welcome you to schedule a consultation at my practice in Central, Hong Kong. We can discuss your specific concerns and explore how psychoanalysis might help.